A Historical Journey Through Traditional African Art

The artistic impulse in Africa stretches back tens of thousands of years, long before recorded history.

African art, often misunderstood or narrowly categorized, is in fact one of the world’s oldest, most diverse, and profoundly significant artistic traditions. Far from being merely decorative or primitive, traditional African art is a complex visual language deeply interwoven with the spiritual, social, political, and daily lives of the communities that create it. To truly appreciate its depth, one must embark on a historical journey, exploring its ancient roots, diverse forms, and the profound functions it served for centuries.

The Earliest Expressions

The artistic impulse in Africa stretches back tens of thousands of years, long before recorded history. Evidence of early artistic expression can be found in rock art scattered across the continent. Sites like the Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria, the Brandberg Mountain in Namibia, and countless caves in the Sahara and Southern Africa reveal intricate depictions of animals, human figures, hunting scenes, rituals, and abstract symbols. These prehistoric paintings and engravings, dating back as far as 28,000 BCE, offer invaluable insights into the daily lives, beliefs, and environments of early African societies. They demonstrate an early mastery of form, perspective, and narrative, laying the groundwork for the sophisticated artistic traditions that would follow.

The Dawn of Civilization

Nigeria, often called the “Giant of Africa,” stands as a crucible of ancient African art, boasting several highly sophisticated pre-colonial artistic cultures that left behind extraordinary legacies.

Nok Culture (c. 1500 BCE – 500 CE): Among the earliest known complex societies in West Africa, the Nok culture is famous for its distinctive terracotta sculptures. Discovered in 1928 near the village of Nok, these figures, often fragmented, are characterized by their elaborate hairstyles, expressive facial features (often almond-shaped eyes and parted lips), and a remarkable sense of naturalism combined with stylization. The purpose of these figures remains somewhat enigmatic, but scholars suggest they may have served ritualistic roles, perhaps representing ancestors, deities, or prominent individuals. The advanced techniques used for firing these large, hollow clay figures indicate a highly skilled and organized society, placing Nok art among the earliest forms of sub-Saharan sculpture.

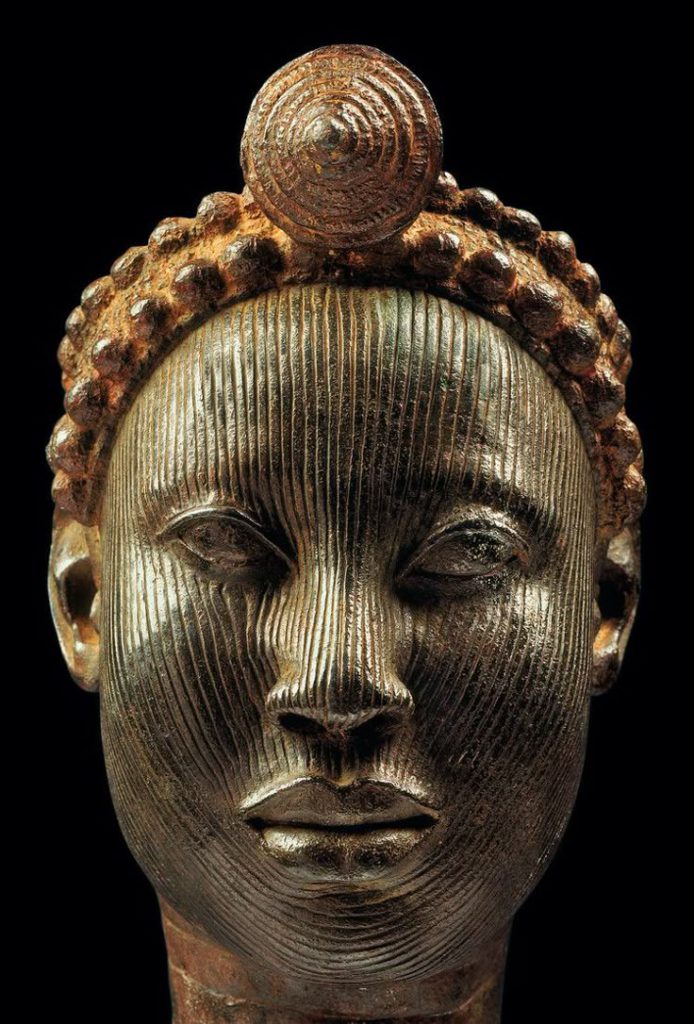

Ife Kingdom (c. 1000 – 1500 CE): Regarded as the spiritual heartland of the Yoruba people, Ife produced some of the most naturalistic and aesthetically refined sculptures in African history. The artists of Ife were masters of both terracotta and bronze casting, creating stunning portrait-like heads, full figures, and masks. These works often depict Oonis (kings), queens, and important figures, characterized by their serene expressions, idealized features, and intricate scarification patterns. The lost-wax casting technique, perfected by Ife artisans, allowed for incredible detail and precision. Ife art was deeply spiritual, believed to be connected to the creation of the world and the origins of Yoruba kingship, functioning as sacred objects for rituals and veneration.

Igbo-Ukwu (c. 9th – 10th Century CE): In southeastern Nigeria, the Igbo-Ukwu site yielded an astonishing collection of bronze and copper artifacts, remarkable for their technical sophistication and elaborate ornamentation. These objects, discovered in the burial chamber of an important dignitary and in a ritual storage pit, include intricate roped pots, ceremonial vessels, and exquisite jewelry. The lost-wax casting technique employed here demonstrated a level of mastery that predates the well-known bronzes of Ife and Benin, suggesting an independent development of this complex metallurgy. The art of Igbo-Ukwu primarily served ceremonial and funerary purposes, reflecting a rich spiritual life and an extensive network of trade that brought valuable materials to the region.

Benin Kingdom (c. 13th – 19th Century CE): Flourishing in what is now Edo State, the Kingdom of Benin created perhaps the most famous and prolific of West African art forms: the Benin Bronzes. These thousands of commemorative plaques, sculptures, and heads, predominantly made from brass (often referred to as bronze), adorned the royal palace and documented the history of the Oba (king) and his court. They depict historical events, rituals, the Oba and his retinue, foreign visitors, and mythological figures. Beyond their aesthetic brilliance, the Benin Bronzes served as a historical archive, a symbol of royal power, and a medium for venerating ancestors. Their sophisticated lost-wax casting technique and their detailed portrayal of court life made them unparalleled, tragically becoming a symbol of colonial plunder after the British Punitive Expedition of 1897.

Diverse Forms Across the Continent

While Nigeria offers a concentrated view of ancient artistic excellence, diverse and equally profound traditions flourished across Africa:

Kongo Kingdom (Central Africa): Renowned for its Nkisi Nkondi power figures—wooden sculptures embedded with nails, blades, and ritual materials—used to activate spiritual forces for justice, healing, or protection. Their expressive forms and accumulated power speak to the potent belief systems they served.

Dogon People (Mali): Famous for their wooden sculptures, often elongated and stylized, depicting ancestors, spirits, and mythological figures. These figures are central to their complex cosmology and used in rituals, particularly those related to fertility and agrarian cycles.

Luba People (DR Congo): Known for their elegant memory boards (Lukasa), intricately carved wooden tablets adorned with beads and shells. These were mnemonic devices used by trained individuals to recall and recount oral histories, genealogies, and cultural knowledge, highlighting art’s role in preserving heritage.

Ashanti People (Ghana): Celebrated for their Kente cloth, a vibrant woven fabric traditionally made from silk and cotton, characterized by intricate geometric patterns, each carrying symbolic meaning related to proverbs, history, and social status. They also produced gold weights (Akan) used for measuring gold dust, which were miniature sculptures depicting animals, people, and abstract forms.

Senufo People (Côte d’Ivoire/Mali/Burkina Faso): Producers of distinctive masks and figures used in the Poro society, an initiation system that educates young men in the responsibilities of adulthood. These masks, often featuring elongated faces and intricate coiffures, represent bush spirits and ancestors, playing crucial roles in rites of passage.

A Symphony of Ingenuity

Traditional African art demonstrates an extraordinary mastery of a wide range of materials and techniques, often chosen for their symbolic significance as much as their aesthetic qualities:

Wood Carving: The most widespread medium, utilizing diverse hardwoods. Techniques varied from rough hewing to intricate detailing, often finished with pigments, oils, or sacrificial libations.

Metalwork (Bronze/Brass, Iron, Gold): Advanced metallurgy, particularly lost-wax casting (as seen in Ife, Igbo-Ukwu, Benin), allowed for the creation of durable and highly detailed works. Iron was vital for tools and ceremonial objects, while gold, especially in West Africa, symbolized royalty and wealth.

Terracotta: Pre-dating metalwork in many areas (e.g., Nok), clay sculptures were modeled and fired, sometimes to immense sizes.

Textiles: Weaving (Kente, Adire, Aso-Oke), dyeing (indigo), appliqué, and embroidery were sophisticated art forms, often imbued with symbolic patterns and colors.

Beadwork: Intricate patterns using glass, shell, or natural beads were used for adornment, regalia, and signifying social status across many cultures (e.g., Yoruba, Zulu).

Natural Materials: Feathers, shells, animal hide, plant fibers, earth pigments, and even human hair were incorporated, reflecting a deep connection to the natural world.

More than Just Aesthetics

Crucially, traditional African art was rarely “art for art’s sake.” Its value lay in its utility and its active role in society:

Spiritual and Religious: Bridging the human and spirit worlds, facilitating communication with ancestors, deities, and nature spirits. Masks, figures, and altars were essential for rituals, divination, and healing.

Social and Political: Affirming leadership, legitimizing power, documenting history, settling disputes, and educating new generations about cultural norms and laws. Royal regalia, commemorative plaques, and prestige objects served these roles.

Educational and Initiatory: Used in rites of passage (birth, puberty, marriage, death) to transmit knowledge, values, and traditions. Masks and figures often embodied teachers or moral lessons.

Utilitarian: Many everyday objects—headrests, stools, containers, spoons—were beautifully crafted, demonstrating that aesthetics and utility were not separate concepts.

Personal Adornment: Body painting, scarification, hairstyles, and jewelry were highly developed art forms communicating identity, status, beauty, and group affiliation.

The historical journey through traditional African art reveals not a monolithic entity, but a vibrant tapestry of diverse cultures, ingenious techniques, and profound philosophies. From the ancient terracottas of Nok to the powerful Nkisi figures of Kongo, and the majestic bronzes of Benin, these artworks stand as testaments to the enduring creativity, spiritual depth, and societal sophistication of African peoples. Understanding this legacy is not just an academic exercise; it is an appreciation of humanity’s shared artistic heritage and a recognition of the profound ways art shapes and reflects life. This traditional foundation provides the crucial context for appreciating the equally dynamic and evolving contemporary African art scene that continues to draw inspiration from these deep roots.