Nigeria’s Ancient Artistic Empires Nok, Ife, Igbo-Ukwu, and Benin

The ancient artistic empires of Nok, Ife, Igbo-Ukwu, and Benin collectively represent a staggering testament to the creative genius and cultural sophistication of pre-colonial Nigeria

Beneath the vibrant surface of modern Nigeria lie the echoes of ancient civilizations, each a crucible of artistic innovation that profoundly shaped not only African art history but indeed, global creative expression. Long before European contact, sophisticated kingdoms flourished, giving birth to distinct sculptural traditions in terracotta and metal that continue to mesmerize and inform us today. From the enigmatic figures of Nok to the lifelike portraits of Ife, the intricate bronzes of Igbo-Ukwu, and the storied plaques of Benin, these enduring masterpieces stand as irrefutable testaments to Nigeria’s unparalleled artistic legacy and its deep-rooted cultural complexity.

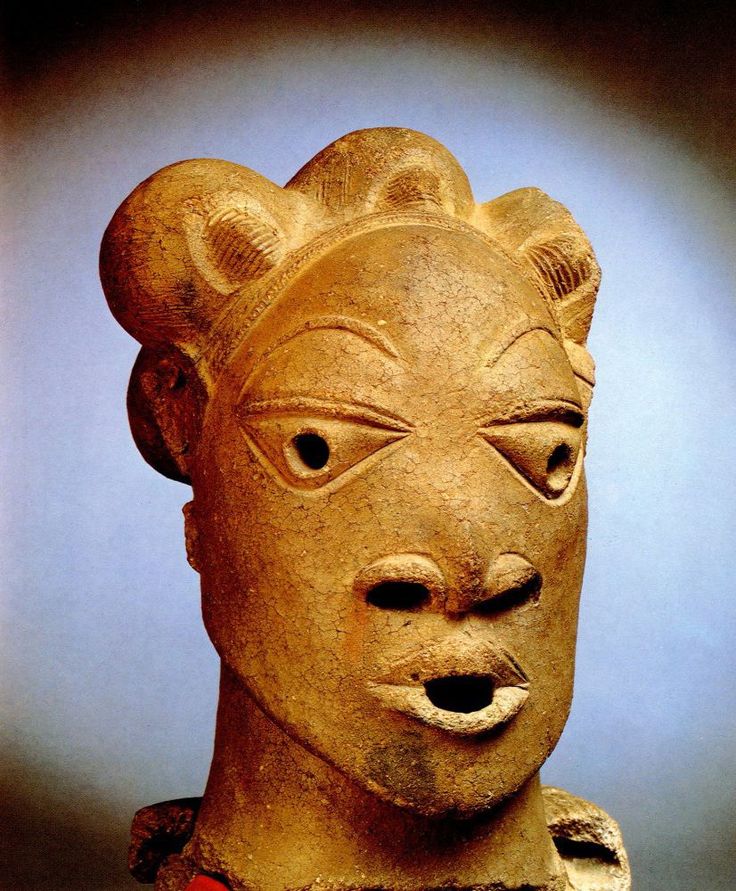

The Enigmatic Smile of Nok: West Africa’s Earliest Sculptors (c. 1500 BCE – 500 CE)

Our journey into Nigeria’s artistic past begins in the central plateau, home to the Nok culture, one of the earliest known centers of iron smelting and sculpture in sub-Saharan Africa. Discovered accidentally in 1928 during tin mining operations near the village of Nok, the distinct terracotta (fired clay) figures unearthed here challenged long-held Western assumptions about the timeline of African artistic development.

Distinctive Style: Nok terracottas are instantly recognizable. They typically feature stylized human and animal figures, often fragmented due to age and erosion. Characteristic human traits include elaborate hairstyles (often braided, beaded, or coiffed), almond-shaped or triangular eyes, pierced nostrils and mouths, and semi-parted lips. While some figures are highly abstracted, others possess a remarkable sense of naturalism, particularly in their facial expressions.

Technical Mastery: The size of some Nok figures (approaching life-size) and their hollow construction indicate a sophisticated understanding of clay properties and firing techniques. These were not simple mud figures but expertly crafted and fired ceramics, demonstrating advanced technological skill for their era.

Purpose and Function: The exact purpose of Nok figures remains a subject of scholarly debate due to the lack of written records. Theories suggest they may have represented ancestors, deities, spiritual guardians, or important community leaders. Their presence in what appear to be ritualistic contexts indicates a strong connection to religious or ceremonial practices. Nok art provides the earliest tangible evidence of complex social structures and developed artistic traditions in West Africa.

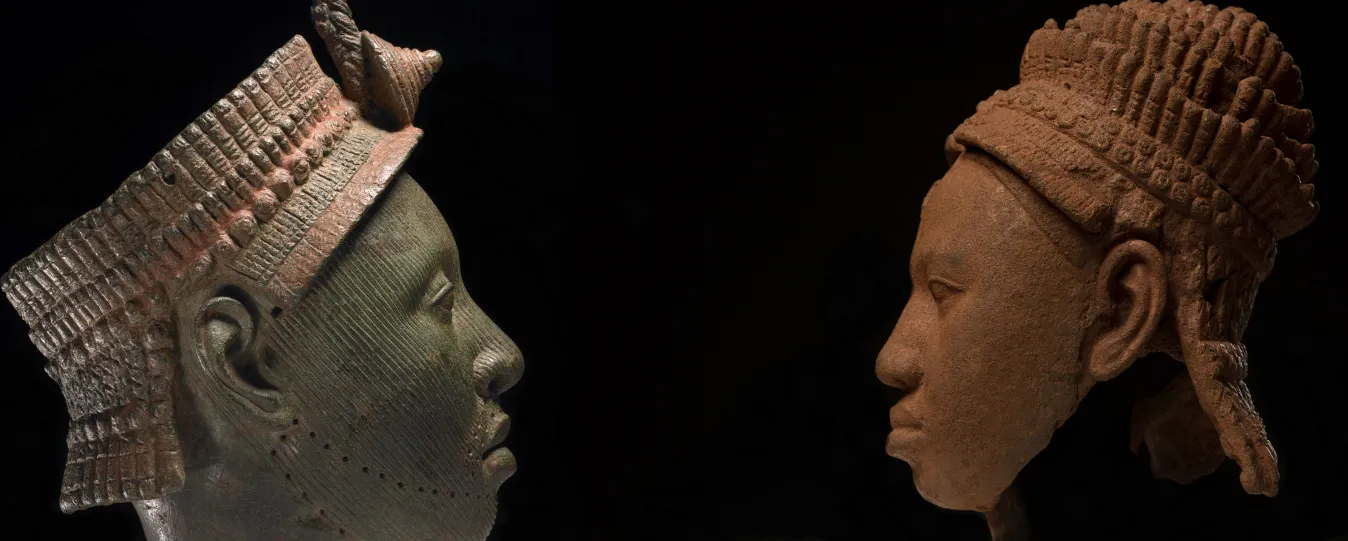

Ife: The Cradle of Realism and Spirituality (c. 1000 – 1500 CE)

Further south, in the southwestern part of Nigeria, flourished the powerful and spiritually significant Yoruba city-state of Ife. Revered by the Yoruba as the birthplace of humanity and the origin of their kingship (Ooni), Ife produced art that stands out for its extraordinary naturalism and technical brilliance in both terracotta and especially bronze.

Stunning Naturalism: Ife art is celebrated for its lifelike and idealized representations of human faces and figures. These portrait-like heads, often depicting Oonis, queens, and other dignitaries, convey a sense of serenity, dignity, and inner calm. Intricate scarification patterns, beadwork, and regalia are meticulously rendered, providing invaluable historical and cultural information.

Lost-Wax Casting Perfection: Ife artisans achieved an astonishing level of mastery in the cire perdue (lost-wax) casting method for their bronze (copper alloy) sculptures. This complex process allowed for incredibly thin castings and minute details, rivaling any metalwork produced globally at the time. The quality and purity of the metals also speak to advanced metallurgical knowledge and extensive trade networks.

Spiritual and Royal Significance: Ife art was deeply entwined with the city’s role as a spiritual and political center. The heads were likely used in ancestral veneration rituals on altars dedicated to deceased Oonis, embodying their spiritual essence and ensuring the continuity of royal authority. Full-figure bronzes also depict deities or important figures in ceremonial contexts.

Igbo-Ukwu: The Enigma of Early Bronze (c. 9th – 10th Century CE)

In southeastern Nigeria, the archaeological site of Igbo-Ukwu revealed another astonishing chapter in Nigeria’s artistic narrative. Discovered in 1938, the site unearthed a collection of bronze and copper artifacts that predated the well-known Ife and Benin bronzes, challenging the chronological understanding of West African metalwork.

Ornate and Intricate: The art of Igbo-Ukwu is characterized by its extraordinary intricacy and decorative flair. The bronzes, primarily ceremonial vessels, staffs, pendants, and elaborate roped pots, are adorned with a bewildering array of motifs: insects, animals, human figures, and highly detailed textures mimicking woven rope or fabric.

Technical Prowess: The artisans of Igbo-Ukwu were masters of the lost-wax casting technique, achieving incredibly thin walls and delicate filigree work, even incorporating intricate, tiny copper spirals onto bronze surfaces. Their use of lead-free bronze alloys was also distinctive.

Purpose and Context: The artifacts were found in three distinct sites: a burial chamber of a high-ranking dignitary, a ritual storage pit, and a refuse pit. This suggests their use in elaborate burial ceremonies, royal regalia, and ritual practices. The wealth of materials, including thousands of glass beads believed to be imported, points to extensive trade networks reaching as far as India, highlighting Igbo-Ukwu’s prosperity and sophisticated social organization.

The Grandeur of Benin: A Kingdom’s Artistic Chronicle (c. 13th – 19th Century CE)

Perhaps the most internationally renowned of Nigeria’s ancient artistic traditions is that of the Kingdom of Benin (not to be confused with the modern Republic of Benin). Flourishing in what is now Edo State, Benin produced an unparalleled corpus of brass plaques, heads, and sculptures that chronicled its history, celebrated its rulers, and adorned its royal palace.

The Benin Bronzes: A Visual Archive: The thousands of “Benin Bronzes” (predominantly brass) are a powerful visual record of the kingdom’s history, depicting key events, royal ceremonies, the Oba (king) and his powerful court, foreign visitors (like the Portuguese), and mythological figures. These plaques were affixed to the wooden pillars of the Oba’s palace, creating a continuous historical narrative.

Lost-Wax Mastery and Stylization: Benin artisans inherited and further refined the lost-wax casting technique, producing works of exceptional quality and detail. While initially influenced by Ife’s naturalism, Benin art developed its own distinct, more formalized and stylized aesthetic, emphasizing symmetry, frontality, and hierarchical scaling (larger figures signify greater importance).

Symbol of Power and Ancestor Veneration: The art of Benin served to glorify the Oba and solidify his divine authority. Commemorative heads of deceased Obas were placed on ancestral altars, infused with spiritual power to ensure the kingdom’s prosperity. Leopards, crocodiles, and serpents—animals associated with the Oba’s power—are recurring motifs.

The 1897 British Punitive Expedition: Tragically, the majority of these invaluable artworks were looted by British forces during a punitive expedition in 1897. Their dispersal into Western museums and private collections sparked a global debate about restitution and colonial plunder, a debate that continues to this day. Despite their controversial acquisition, the Benin Bronzes remain among the most significant artistic achievements in human history.

A Legacy Uninterrupted

The ancient artistic empires of Nok, Ife, Igbo-Ukwu, and Benin collectively represent a staggering testament to the creative genius and cultural sophistication of pre-colonial Nigeria. These civilizations, with their distinct styles, advanced techniques, and profound functional purposes, did not merely produce beautiful objects; they created living archives, spiritual conduits, and symbols of power that shaped the very fabric of their societies. Their enduring masterpieces are not relics of a distant past but vibrant testaments to an uninterrupted legacy of Nigerian artistic excellence, a foundation upon which the rich tapestry of modern and contemporary Nigerian art continues to be woven.