A Historical Journey Through African Jewelry

Before the rise of empires or the invention of writing, humans adorned themselves. In Africa, this fundamental impulse to beautify and signify transformed simple materials into profound statements, weaving a rich tapestry of history, identity, and spiritual belief. African jewelry is not merely decorative; it is an enduring language, a chronicle etched in shells, beads, metals, and natural fibers, telling stories of ancient civilizations, sophisticated craftsmanship, and the ever-evolving human spirit. To truly appreciate its depth, we must embark on a historical journey, tracing its origins from millennia past to its complex forms and changing roles across the continent.

Prehistoric Roots

The earliest evidence of human adornment often points to Africa. Archaeological discoveries reveal that early hominids adorned themselves with natural materials long before the advent of complex societies:

Shell Beads: One of the most significant finds comes from the Blombos Cave in South Africa, where perforated Nassarius snail shells, dating back an astonishing 75,000 to 100,000 years, are considered among the world’s oldest known jewelry. These deliberately modified shells suggest symbolic thought and the practice of personal adornment as a form of communication.

Ostrich Eggshell Beads: Across various sites, particularly in Eastern and Southern Africa, perforated ostrich eggshell beads have been found, dating back tens of thousands of years. Their widespread presence indicates early networks of exchange and a universal human desire for personal expression.

Natural Materials: Early forms of adornment would have included readily available materials like animal teeth, bones, seeds, stones, and plant fibers, fashioned into necklaces, bracelets, and hair decorations. These rudimentary forms laid the groundwork for future sophisticated techniques.

These prehistoric artifacts underscore that adornment in Africa was not a late development but an intrinsic part of human culture from its very beginnings, serving perhaps as identifiers of groups, status, or spiritual beliefs.

Ancient Kingdoms and Civilizations

As complex societies and kingdoms emerged across Africa, so too did more sophisticated forms of jewelry, driven by new technologies, trade networks, and evolving social structures.

Ancient Egypt (c. 3100 BCE – 30 BCE): While often viewed separately, ancient Egypt is undeniably part of Africa’s rich heritage. Its jewelry was unparalleled in its opulence, craftsmanship, and symbolic complexity.

Materials: Gold, silver, lapis lazuli, turquoise, carnelian, amethyst, and glass were expertly worked into intricate pieces.

Forms: Broad collars (usekh collars), pectorals, bracelets, anklets, rings, and diadems were common.

Symbolism: Every piece was laden with meaning. Scarabs symbolized rebirth, the ankh represented life, and the Eye of Horus offered protection. Jewelry indicated social status, religious devotion, and was essential for both the living and the deceased, accompanying individuals into the afterlife. The techniques, including cloisonné, granulation, and inlay, were highly advanced.

Nok Culture (c. 1500 BCE – 500 CE, Nigeria): While primarily known for its terracotta sculptures, the Nok culture also likely produced forms of personal adornment, though direct archaeological evidence of perishable jewelry is scarce. However, the elaborate hairstyles and detailed facial features on their sculptures suggest a society with an interest in complex personal presentation, indicating that other forms of beautification and adornment were likely present.

Ife Kingdom (c. 1000 – 1500 CE, Nigeria): The artists of Ife were masters of naturalistic sculpture, and their depictions provide valuable insights into the adornment of their time.

Beads: Ife sculptures frequently depict individuals wearing intricate beaded necklaces, bracelets, and crowns, suggesting the importance of beadwork, particularly coral and imported glass beads, as markers of royalty and status.

Bronze and Copper: While large sculptures are famous, smaller bronze and copper ornaments were likely produced, utilizing their advanced metallurgical skills.

Benin Kingdom (c. 13th – 19th Century CE, Nigeria): The Kingdom of Benin developed an extraordinary tradition of royal regalia and jewelry, particularly after contact with the Portuguese introduced new materials like coral and more extensive trade in brass.

Materials: Coral beads (prized for their rarity and connection to the sea god Olokun), brass, ivory, and imported European glass beads were prominent.

Forms: Elaborate coral bead crowns (ukpe-okhue), collars, necklaces, bracelets, and anklets were essential components of the Oba’s (king’s) ceremonial attire. Ivory armlets carved with intricate scenes also denoted power.

Symbolism: These pieces were not just beautiful; they were infused with ancestral power and served as potent symbols of the Oba’s divine authority, wealth, and the kingdom’s history. The weight and complexity of the coral regalia were direct representations of the Oba’s immense power.

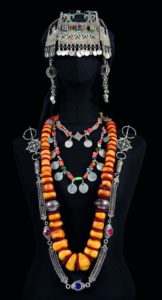

Across the Continent

Beyond these major historical centers, diverse and equally rich traditions of jewelry and adornment flourished across the African continent, each reflecting local resources, cultural beliefs, and aesthetic preferences.

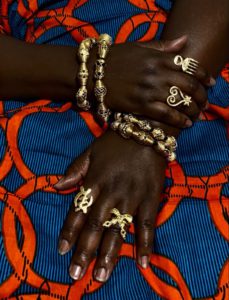

West Africa (e.g., Akan, Mali, Senegal):

Gold: The Akan people of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire were renowned for their sophisticated gold jewelry, using techniques like lost-wax casting, repoussé, and granulation to create elaborate pendants (forowa), rings, and beads. Gold symbolized royalty, purity, and spiritual potency.

Beads: Trade beads (Venetian, Islamic) became highly valued, often integrated into intricate necklaces and body adornments by groups like the Krobo of Ghana or the Fulani.

East Africa (e.g., Maasai, Turkana):

Beadwork: Communities like the Maasai, Samburu, and Turkana are famous for their vibrant and complex beadwork. Glass beads (often imported) are meticulously strung onto wire or hide to create elaborate collars, necklaces, earrings, and armbands. The patterns, colors, and arrangement often signify age-sets, marital status, courage, and social hierarchy.

Metal: Iron and copper were also used for bracelets, anklets, and ear ornaments.

Southern Africa (e.g., Zulu, Ndebele):

Beadwork: The Zulu and Ndebele peoples are celebrated for their highly symbolic and geometric beadwork. Ndebele women, for example, wear incredibly elaborate beaded neck rings (idzilla) and aprons, signifying status and life stages.

Natural Materials: Seeds, grasses, and animal products were also extensively used for adornment.

Central Africa (e.g., Kuba, Luba):

Shells and Beads: Cowrie shells, once a form of currency, were widely used for adornment, symbolizing wealth and fertility. Glass beads and local materials were combined to create intricate patterns on clothing, masks, and personal jewelry.

Copper and Iron: Metal armlets and anklets were common, often signifying status or spiritual protection.

The Evolution of Role

Over millennia, the role of jewelry in Africa evolved, though its core functions remained strong:

Spiritual and Protective: Early forms of jewelry often served as talismans or amulets, believed to ward off evil, bring good fortune, or connect the wearer to ancestral or divine forces.

Social Identity and Status: Jewelry became a powerful visual language communicating a person’s age, marital status, and initiation into secret societies, achievements, wealth, and social standing. Different beads, metals, or patterns could instantly convey complex information about the wearer.

Aesthetic Expression: While always functional, the sheer artistry and beauty of African jewelry cannot be overlooked. The desire to create aesthetically pleasing objects was a constant driving force.

Economic Value: Certain types of jewelry, particularly gold, silver, and rare beads, also served as forms of portable wealth and investment, easily transported and traded.

A Legacy of Enduring Significance

The historical journey through African jewelry reveals a continuous tradition of unparalleled artistry and profound cultural significance. From the earliest shell beads in South Africa to the regal gold work of the Akan and the intricate coral of Benin, African adornment has always been more than mere decoration. It is a powerful enduring language—a testament to human creativity, resourcefulness, and the universal desire to express identity, belief, and status. This deep historical foundation continues to inform and inspire the vibrant contemporary jewelry scene in Africa and beyond, ensuring that this ancient language of adornment remains as relevant and resonant today as it was tens of thousands of years ago.