Hair, Gele, and Body Adornment as Distinct Art Forms in Nigeria

In Nigeria, the canvas for artistic expression extends far beyond a sculptor’s wood or a weaver’s loom; it encompasses the human body itself. Hair, skin, and fabric are meticulously transformed into a dynamic visual language, communicating identity, status, celebration, and spiritual connection. From the intricate artistry of hair braiding and the architectural marvels of the gele (headtie) to subtle body modifications and temporary adornments, these practices represent a profound continuum of artistic innovation, deeply woven into the fabric of Nigerian social and cultural life. They are not mere fashion statements, but living art forms, constantly evolving yet rooted in centuries of tradition and meaning.

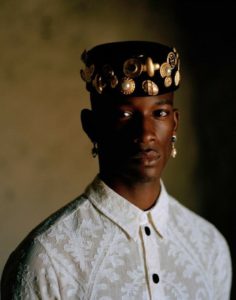

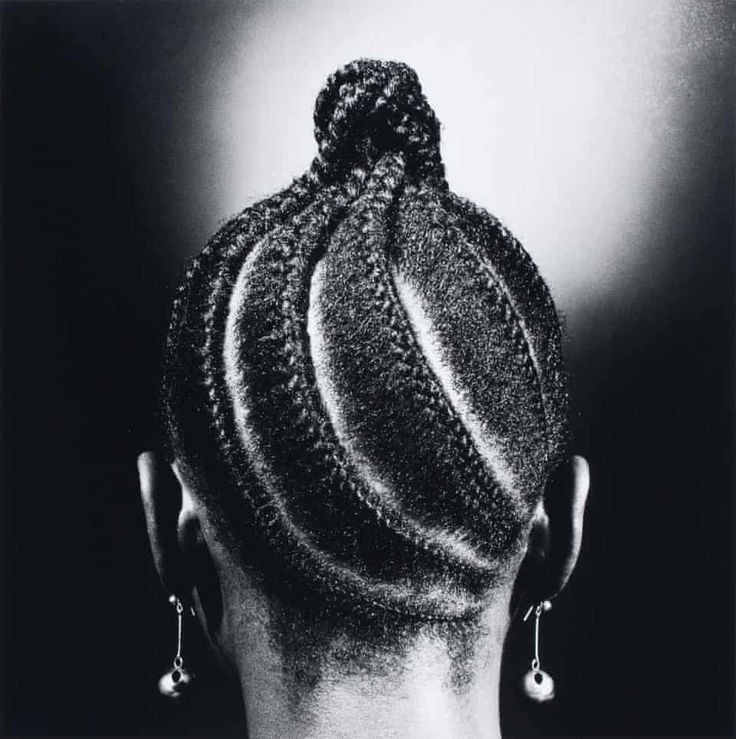

I. The Art of Hair

Hair in Nigeria is arguably one of the most expressive and culturally significant forms of adornment. It is a powerful marker of ethnic identity, social status, age, and personal style, often requiring immense skill and patience.

Braiding and Plaiting (e.g., Suku, Dada, Cornrows):

Diversity of Styles: Nigerian hair braiding encompasses a vast array of styles, each with specific names, origins, and meanings. These range from tightly woven cornrows (idun among Yoruba, gwàl among Hausa) that lie flat against the scalp, to elaborate free-hanging braids, twists, and locs.

Ethnic Identity: Specific patterns and techniques are often unique to particular ethnic groups, allowing for instant recognition of a person’s heritage. For example, the suku (basket-like crown) style is characteristic of the Yoruba.

Symbolism: Hairstyles can convey marital status (e.g., a style worn by a married woman), mourning, celebration, or even preparation for ritual. The direction of braids, the number of sections, and the accessories used all contribute to the message.

Community and Skill: Hair braiding is often a communal activity, fostering social bonds. The skill of the braider is highly valued, capable of transforming hair into complex, often architectural, designs.

Natural Hair Movement: In contemporary Nigeria, there’s a strong resurgence and celebration of natural hair textures and traditional styles, often adorned with beads, cowrie shells, or metallic rings.

Hair Adornments

Beads and Cowries: Historically and presently, various types of beads (glass, coral, metal) and cowrie shells are integrated into braids or attached to the ends, adding color, weight, and symbolic meaning (wealth, fertility).

Threads and Fibers: Colored threads or extensions made from natural fibers are often interwoven to add length, volume, and color, enhancing the complexity of the styles.

II. The Grandeur of the Gele

The gele is a headtie, typically made from a stiff, elaborate fabric, meticulously folded, pleated, and tied into sculptural forms. It is particularly prominent among the Yoruba, but its popularity has spread across Nigeria and the diaspora, becoming an iconic symbol of Nigerian fashion and celebration.

Artistry and Skill:

Tying a gele is an art form that requires considerable skill and practice. The final shape can range from elegant and understated to towering and elaborate, creating a dramatic silhouette.

Styles: There are numerous tying styles, often with evocative names, and trends evolve constantly. Some gele styles are so complex they are considered architectural feats of fabric manipulation.

Materials:

Gele fabric is typically stiff, lustrous, and often richly patterned. Popular materials include Aso-Oke (hand-woven fabric), lace, satin, and various embellished textiles. The fabric itself adds to the visual richness.

Symbolism and Occasion

Celebration: The gele is synonymous with celebrations – weddings, naming ceremonies, festivals, and religious gatherings. It signifies readiness for celebration and a high level of personal presentation.

Status and Wealth: The quality of the fabric, the intricacy of the tie, and the overall grandeur of the gele can subtly communicate wealth, social status, and personal taste.

Completing the Ensemble: It is considered an essential part of formal traditional attire, completing the look and framing the wearer’s face.

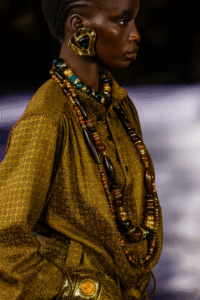

III. Body Adornment

While distinct from detachable jewelry, other forms of body adornment play a crucial role in Nigerian beautification practices, transforming the skin itself into a site of artistic expression.

Traditional Body Painting and Henna (Lalle):

Lalle (Henna): Particularly prevalent in Northern Nigeria among the Hausa and Fulani, lalle is the application of henna paste to the hands and feet to create intricate, often floral and geometric, patterns. It is central to celebrations like weddings, Sallah festivals, and naming ceremonies, symbolizing beauty, blessing, and celebration. The designs are often incredibly detailed and temporary.

Indigenous Body Painting: Historically, and in some rural areas still, various ethnic groups used natural pigments (from clay, plants, charcoal) to paint the body for rituals, initiations, and specific ceremonies. These patterns often had spiritual significance or marked transitions.

Uli Art (Igbo): While also applied to murals, Uli designs are historically a significant form of body painting among Igbo women, characterized by flowing, curvilinear lines and abstract motifs. These designs, often applied during festivals or for special occasions, enhanced beauty and signified grace and feminine ideals.

Waist Beads (Ileke Idi / Jigida):

Worn by women across many Nigerian ethnic groups, waist beads are highly personal and often concealed.

Symbolism: They serve multiple purposes:

Beauty and Sensuality: Worn for their aesthetic appeal and perceived allure.

Weight Monitoring: Some women use them to track changes in their waistline.

Femininity and Maturity: Can signify a woman’s transition into adulthood or marriage.

Spiritual Protection: Some beads are charmed for protection or to enhance fertility.

Tradition: Often gifted at birth or initiation, passed down through generations.

Scarification:

Historically, scarification was practiced by various Nigerian ethnic groups (e.g., Yoruba, Igbo, Tiv, Igala) to create permanent marks on the skin.

Purpose: These patterns served as indelible ethnic markers, signifying tribal identity, clan affiliation, social status, bravery, and beauty standards. They could also have spiritual or protective functions. While less common today, historical photographs and accounts reveal the immense artistry involved in their creation.

IV. Interplay with Jewelry and Clothing

These forms of bodily adornment are rarely seen in isolation. They are intricately woven into the broader tapestry of Nigerian fashion and personal presentation. A beautifully braided hairstyle might be adorned with precious beads, perfectly complementing a flowing Aso-Oke garment and layered necklaces. The gele itself dictates the proportion and style of accompanying jewelry. This holistic approach to beautification creates a powerful, unified aesthetic that is both stunning and deeply meaningful.

A Dynamic Expression of Self and Culture

The Nigerian body, adorned with meticulously styled hair, majestically tied gele, and intricately painted skin, stands as a testament to a rich and dynamic artistic heritage. These practices are far more than superficial beautification; they are profound expressions of identity, social communication, spiritual belief, and artistic innovation. Continuously evolving yet deeply rooted in tradition, these forms of adornment showcase Nigeria’s unparalleled creativity and its unique philosophy that views the human form itself as a living canvas, embodying the spirit of a vibrant and expressive culture.