African Art’s Global Footprint and Influence on Western Modernism and the Diaspora

The global footprint of African art is undeniable. Its initial impact on Western Modernism revolutionized artistic thought, liberating artists from previous constraints and ushering in new forms of expression.

For centuries, African art was often dismissed or exoticized by Western observers, labeled as “primitive” or mere ethnographic curiosities. Yet, at the turn of the 20th century, a profound shift occurred: European artists, disillusioned with the rigid academic traditions and seeking new forms of expression, “discovered” African art. This encounter ignited a revolutionary transformation in Western art, providing a powerful impetus for Modernism. Simultaneously, African aesthetic principles journeyed across the Atlantic, influencing the artistic expressions of the African diaspora, giving rise to unique and powerful movements.

The “Discovery” and the Birth of Western Modernism

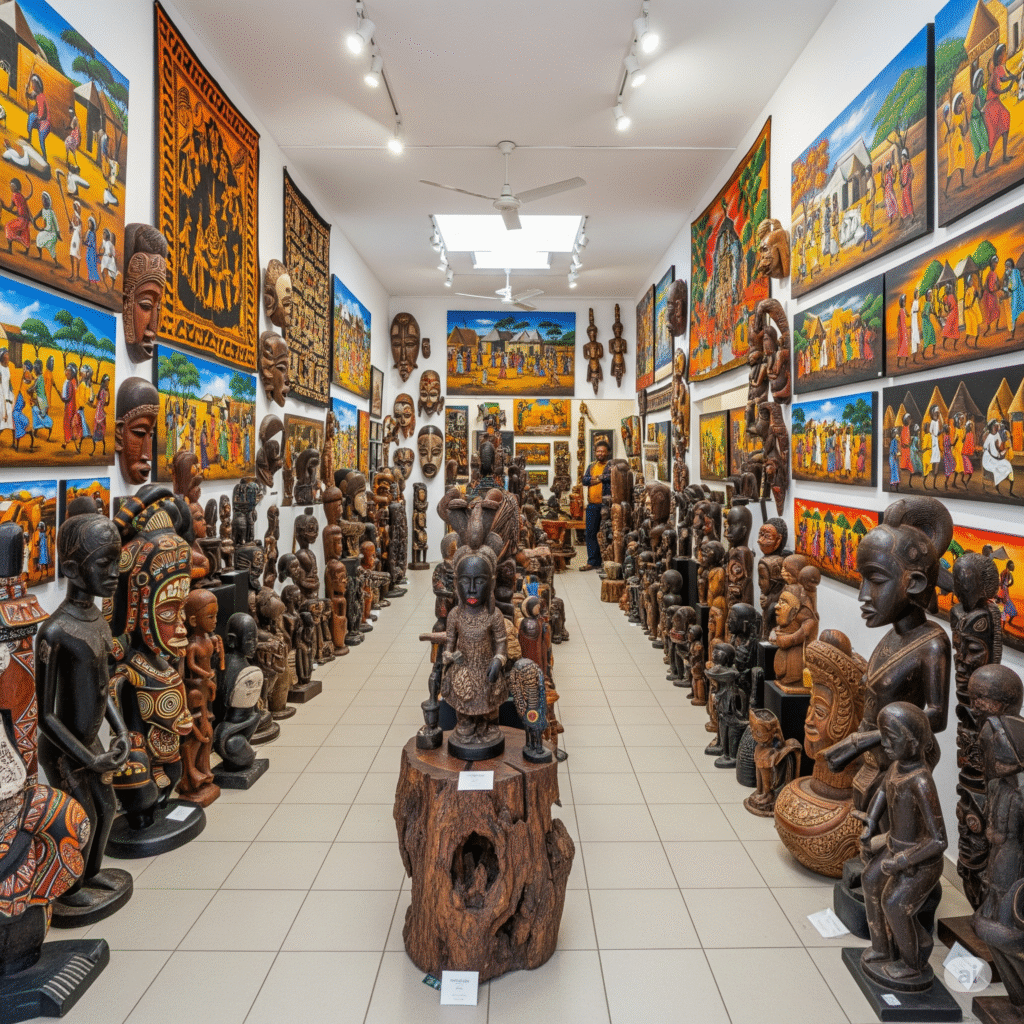

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw increasing colonial expansion and ethnographic expeditions, leading to a flood of African artifacts into European museums and private collections. While initially displayed as anthropological specimens, these objects soon captured the imagination of a generation of avant-garde artists in Paris and Berlin.

Breaking with Tradition: Western art was steeped in naturalism, realism, and classical ideals. African sculpture, with its bold simplification of forms, exaggerated features, angularity, and disregard for conventional perspective, offered a radical alternative. It presented a compelling path away from the limitations of mimetic representation.

Pablo Picasso and Cubism: The most famous and pivotal encounter was that of Pablo Picasso at the Trocadéro Museum in Paris around 1907. He was struck by the raw power and expressive force of African masks and sculptures, particularly those from West Africa (like masks from the Dan, Grebo, or Fang peoples).

Picasso famously stated, “The masks were not just sculptures. They were magical objects… They were weapons to keep people from being ruled by spirits… The Demoiselles d’Avignon must have been an exorcism.”

This “revelation” directly influenced his groundbreaking work, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), where the faces of the women on the right side bear striking resemblances to Iberian sculpture and African masks, particularly in their angularity and simplified, geometric forms.

This shift directly paved the way for Cubism, where objects were analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstracted form—a direct conceptual parallel to the way African artists abstracted human and animal forms to emphasize symbolic or spiritual qualities rather than strict naturalism.

The Expressionists (Die Brücke & Der Blaue Reiter): German Expressionists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff were also profoundly moved by African and Oceanic art. They were drawn to its perceived “primitivism,” raw emotional intensity, and spiritual depth, which they saw as a pure, uncorrupted form of expression.

They incorporated the angularity, stark contours, and emotive distortion found in African masks and figures into their paintings and sculptures, seeking to express inner feelings rather than outer appearances.

Henri Matisse and Fauvism: While perhaps less direct than Cubism, Matisse was also an admirer of African art, particularly its decorative qualities and the use of bold, non-naturalistic color. The simplified forms and rhythmic patterns found in African textiles and masks influenced his approach to form and color, contributing to the vibrant, expressive qualities of Fauvism.

Constantin Brâncuși and Sculpture: The Romanian sculptor Brâncuși, a pioneer of modern sculpture, was influenced by the reductive and pure forms found in African carving. His highly simplified, abstract forms, emphasizing essential volumes, echo the timeless and monumental qualities of many African sculptures.

It’s crucial to acknowledge the problematic context of this “discovery”: African art was largely encountered through colonial plunder and often admired without genuine understanding of its cultural significance or acknowledgement of its creators. Yet, its aesthetic and conceptual impact on Western Modernism was undeniable and transformative, ushering in an era of artistic experimentation and abstraction.

African Art in the Diaspora: Reclaiming Identity and Heritage

Parallel to its impact on Western art, African aesthetics also played a vital, though often different, role in the artistic expressions of the African diaspora—communities of African descent scattered globally, particularly in the Americas and the Caribbean, due to the transatlantic slave trade. Here, African art wasn’t a “discovery” but a reconnection, a reclamation of lost heritage, and a powerful tool for identity formation and resistance.

The Harlem Renaissance (1920s-1930s): This vibrant cultural movement in the United States saw Black artists, writers, and musicians drawing inspiration from their African roots to forge a distinct African American identity.

Artists like Aaron Douglas (known as the “Father of African American Art”) incorporated simplified, geometric forms, silhouetted figures, and African motifs into his murals and illustrations, drawing directly from African sculpture and patterns to depict Black history and pride.

Others, like Augusta Savage (sculptor) and James VanDerZee (photographer), celebrated Black life and culture, subtly infusing their work with a sense of dignity and resilience that echoed the spirit of African art.

Negritude Movement (1930s-1950s): Originating among Francophone intellectuals and artists in Paris (e.g., Léopold Sédar Senghor, Aimé Césaire), Negritude sought to reclaim and celebrate Black identity, culture, and values in response to colonialism and racism.

While primarily literary, the movement heavily influenced visual artists who sought to express the unique “Black aesthetic” and valorize African heritage, often incorporating traditional motifs and emphasizing the strength and beauty of the Black form.

Caribbean and Latin American Art: African artistic and spiritual traditions profoundly influenced the syncretic cultures of the Caribbean and parts of Latin America.

Vodou flags (Haiti): These dazzling, often beaded, ceremonial flags incorporate West African Vodun symbols and aesthetics, serving both religious and artistic functions.

Santería and Candomblé art (Cuba, Brazil): Figures and altars for Orishas (deities of Yoruba origin) are direct descendants of West African spiritual art, adapted and evolved within new contexts.

Artists like Wifredo Lam (Cuba) combined Surrealism with Afro-Cuban motifs, creating powerful works that explored hybrid identities and spiritual traditions.

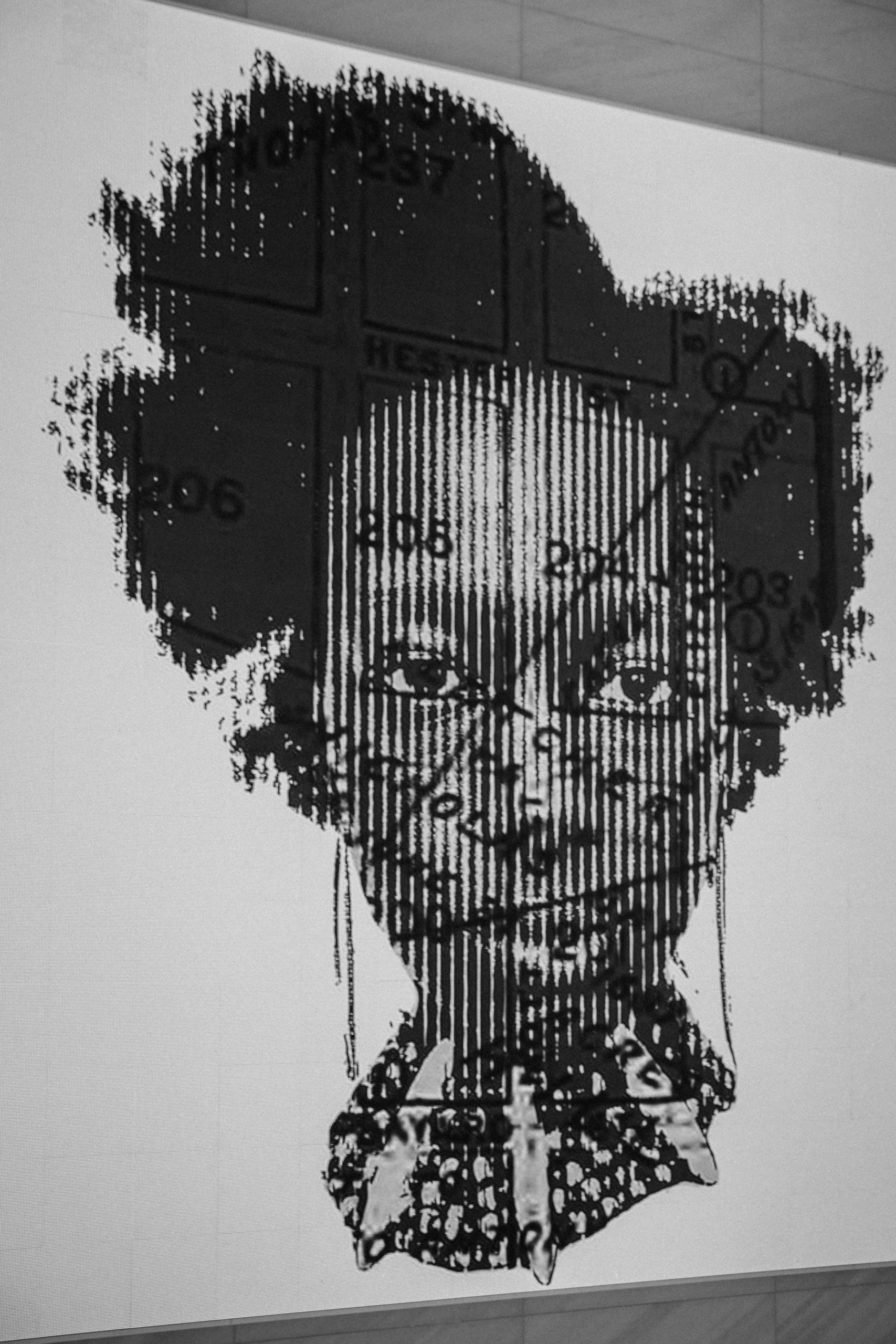

Contemporary Diaspora Art: Today, artists of African descent continue to engage with their ancestral heritage in diverse ways.

They reinterpret traditional symbols, forms, and philosophies through contemporary mediums (painting, sculpture, installation, digital art) to explore themes of identity, migration, colonialism, racism, and the enduring strength of African culture.

Artists like El Anatsui (Ghanaian, working globally) uses discarded materials like bottle caps to create monumental tapestries that evoke traditional African textiles while commenting on consumerism and history—a powerful example of how ancient craft traditions can inform contemporary global narratives.

A Legacy of Enduring Influence

The global footprint of African art is undeniable. Its initial impact on Western Modernism revolutionized artistic thought, liberating artists from previous constraints and ushering in new forms of expression. Simultaneously, within the African diaspora, it provided a vital link to ancestral heritage, fostering movements of self-affirmation and cultural pride.

Today, this influence continues to expand. Contemporary African and diaspora artists are not only reclaiming their narrative but are actively shaping global art conversations, proving that the creative roots of Africa run deep, nourishing diverse artistic trees across continents and continually pushing the boundaries of what art can be. The conversation around African art has shifted from “discovery” to recognition, from influence to direct participation, acknowledging its central place in the ongoing story of global art history.