Adornment in Ritual and Royalty: Crowns, Beads, and the Language of Power in African Kingdoms

Across Africa, adornment has always been more than elegance, it is authority made visible. In ancient palaces, royal courts, and sacred shrines, crowns, beads, and ornaments served as living symbols of divine right and ancestral connection. They were not simply decorative; they were declarations of power, continuity, and cosmic order.

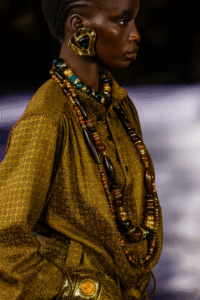

From the coral regalia of the Benin Kingdom to the beaded crowns of Yoruba kings and the golden ornaments of Akan rulers, adornment was and still is the language through which African royalty communicates spiritual legitimacy and leadership.

The Royal Aesthetic: Beauty as Sovereignty

In traditional African societies, beauty was inseparable from authority. A king or queen was expected to radiate not only wisdom and courage but also spiritual splendor. Their adornment represented balance between heaven and earth, the ancestors and the living, the seen and unseen worlds.

The splendor of their regalia signaled divine approval. It was believed that a ruler’s brilliance reflected the favor of the gods. Every bead, feather, and metal ornament carried sacred meaning, turning the body of the monarch into a moving altar of heritage.

The Benin Kingdom: Coral and Power

One of the most iconic symbols of African royal adornment comes from the Benin Kingdom (in present-day Edo State, Nigeria). The Oba of Benin’s regalia is a spectacle of artistry, layers of coral beads, ivory bracelets, and carved pendants that shimmer in ritual significance.

Coral, known locally as ivie, is more than a gem; it is sacred. It represents life, blood, wealth, and protection. The Oba’s coral regalia is believed to carry spiritual power connecting him directly to Olokun, the deity of the sea, prosperity, and fertility.

During coronation and festival ceremonies, the Oba’s entire body gleams in coral: a beaded crown (okpoho), chest plates, anklets, and neck strands. This display is not vanity, it is a spiritual armor. The coral “breathes life” into the king, enabling him to channel divine authority and safeguard his people.

“The king does not wear beads, the beads wear the king,” says a Benin proverb, affirming that regalia and ruler are spiritually bound.

The Yoruba Beaded Crown: A Portal Between Worlds

In Yoruba culture, the crown (Ade) is considered the highest and holiest symbol of kingship. It is not just a headpiece but a living deity, a vessel of ancestral energy and divine wisdom. The Yoruba believe that the Oba (king) is the representative of Oduduwa, the progenitor of their people, and that his crown connects him to the spiritual realm.

A Yoruba beaded crown often contains hundreds of glass beads in red, blue, white, and gold each color holding ritual significance. The veil of beaded strands that fall over the Oba’s face symbolizes mystery and reverence, concealing his human features and revealing his divine identity.

During coronation, the crown is awakened with sacred chants and offerings. Once placed on the Oba’s head, it transforms him into a mediator between his ancestors and his people, an embodiment of cosmic order.

“A crown without a spirit is a hat,” goes an old Yoruba saying. “But a crown with spirit is a kingdom.”

Gold and Divinity in Akan Royalty

Among the Akan people of Ghana, especially the Ashanti Kingdom, gold is the emblem of immortality and divine kingship. The Akan believe that gold contains the kra, or life force of the sun. Therefore, gold jewelry and regalia are used to express spiritual power, not material wealth.

The Asantehene (king of the Ashanti) is often adorned in gold bracelets, necklaces, and anklets — each crafted with intricate patterns symbolizing virtues like bravery, justice, and unity. The Golden Stool, which holds the soul of the Ashanti nation, is never sat upon, only revered.

To wear gold in Akan culture is to channel the brilliance of the ancestors and the gods to shine as a custodian of divine energy.

Adornment in Ritual Contexts

Beyond royalty, adornment also plays a crucial role in ritual ceremonies, from initiations to harvest festivals and spiritual invocations. Priests, priestesses, and healers use jewelry, shells, feathers, and beads as spiritual tools to communicate with deities.

Cowrie shells, for example, symbolize wealth and feminine power in many traditions. In divination, they serve as mediums for speaking with spirits. In ritual dance, beaded belts and bracelets jingle with movement, activating energy and rhythm.

In some cultures, initiates wear specific adornments that mark their transformation, from youth to adulthood, or from the uninitiated to the spiritually awakened. The jewelry acts as both protection and proclamation of new identity.

Adornment as Living Heritage

What makes African adornment remarkable is its continuity. Despite colonization, religious shifts, and globalization, these traditions have survived, not just in museums or rituals, but in everyday life and fashion.

Modern African designers reinterpret crowns, beads, and gold through contemporary lenses. Coral-inspired necklaces, beaded cuffs, and regal headpieces now appear on runways from Lagos to Paris. Yet, even in reinvention, the symbolism remains intact, beauty as ancestry, design as divinity.

Fashion houses like Ejiro Amos Tafiri and Ohema Ohene often draw inspiration from royal aesthetics, reminding the world that Africa’s sense of grandeur predates the modern concept of luxury.

The Sacred Language of Adornment

Each African kingdom developed its own symbolic grammar of adornment, a language of color, texture, and material that told stories of origin, courage, and belief. A single bead could mark lineage, a bracelet could declare status, and a crown could unite heaven and earth.

Adornment thus became both history and prophecy, worn not only to remember the past but to invoke the future. It connected the individual to the collective, and the living to the ancestors.

The Crown Still Shines

The tradition of royal and ritual adornment in Africa continues to remind us that beauty is not superficial, it is sacred communication. Crowns, beads, and gold tell us who we are and where we come from. They are vessels of spirit, symbols of unity, and reminders of Africa’s unbroken dignity.

When an African monarch walks in coral and gold, it is not a performance, it is a prayer.

When a priestess beads her wrists before dawn, it is not fashion, it is faith.

When a modern African woman adorns herself in Afrocentric jewelry, she joins a continuum of power stretching back to the first queens of the continent.

Adornment is, and always has been, the African language of royalty, where the divine finds its crown.